Posts Tagged ‘assessment’

Assessing STE(A)M Learning

In Learning in the Making, I discuss assessment as follows:

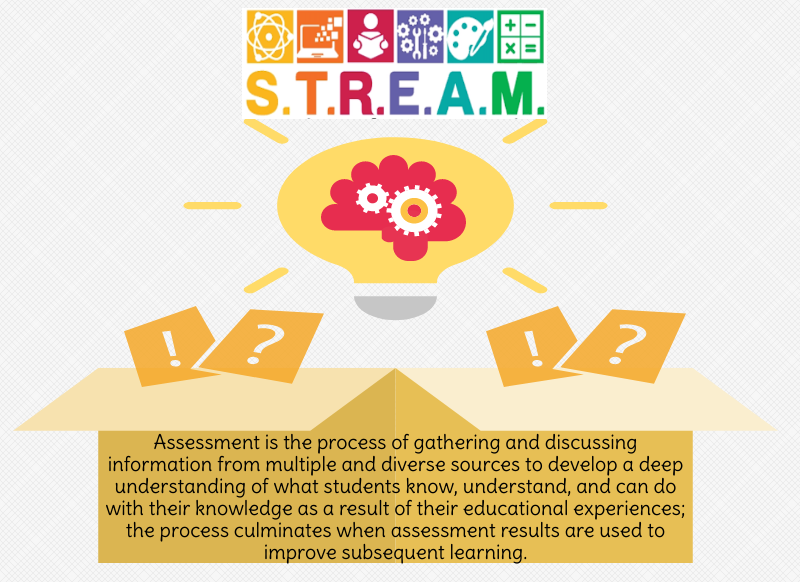

Educators should be clear about how and why they include assessment in their instruction. They need to be strategic and intentional in its use. Assessment should be about informing learners about their performance so increased learning and future improvements can result. “Assessment is the process of gathering and discussing information from multiple and diverse sources in order to develop a deep understanding of what students know, understand, and can do with their knowledge as a result of their educational experiences; the process culminates when assessment results are used to improve subsequent learning” (Huba & Freed, 2000, p. 8).

During Fall, 2019, I taught a graduate level STE(A)M [Science, Technology, Engineering, (Arts), Math] course for Antioch University. Their last major assignment was to create methods for assessing STE(AM) learning. My goal was for the students, who are classroom teachers, to develop assessment strategies based on above. The description of the assignment follows:

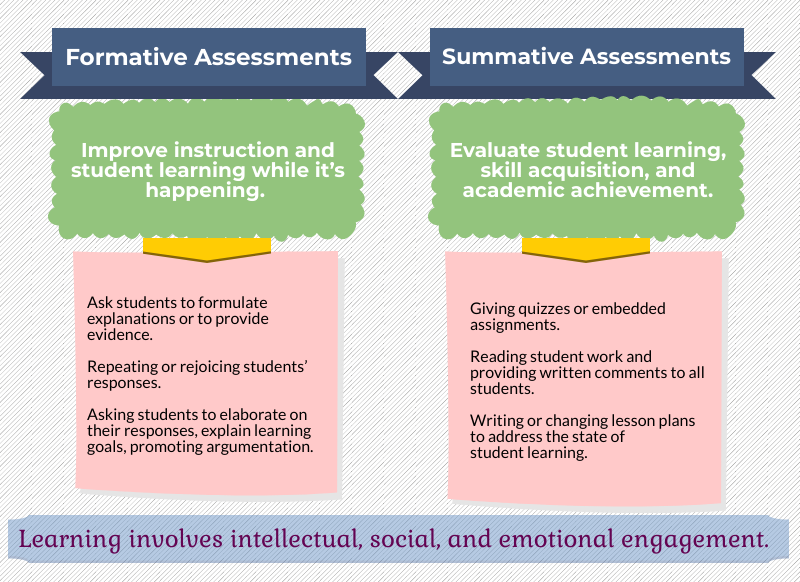

Create a list possible strategies to assess students STEM/STEAM projects. It should be tailored to the (expected) age level of your learners, the focus of your learning activities (STEM, STEAM, or STREAM). Discuss several forms of formative and summative assessments that you can draw upon when you teach STEAM-based lessons. Review the following:

- Documenting Learning: http://www.documenting4learning.com/

- Teaching Tools or STEM Education – Assessment: http://stemteachingtools.org/tgs/Assessment

- Assessing Maker Education Projects – https://usergeneratededucation.wordpress.com/2018/05/05/assessing-maker-education-projects/

- Beyond the Rubric – https://makered.org/beyondrubrics/toolkit/

- Pinterest Aggregate – Assessment Resources https://www.pinterest.com/criticalskills1/assessment/

- 75 Digital Tools and Apps Teachers Can Use to Support Formative Assessment in the Classroom https://www.nwea.org/blog/2019/75-digital-tools-apps-teachers-use-to-support-classroom-formative-assessment/

In developing your strategies and ideas include at least one strategy from each of the following:

- Documenting Learning Strategies (formative)

- Reflecting on Learning (formative)

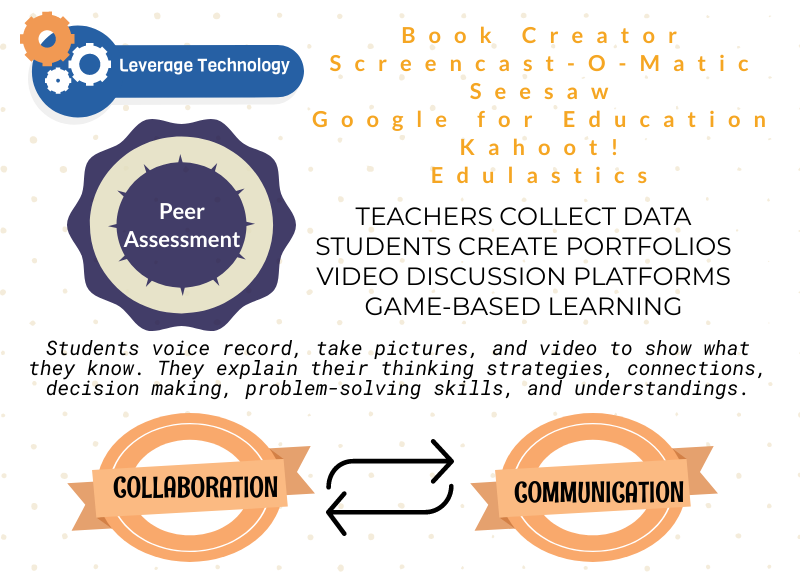

- Strategies that Leverage Technology, e.g., blogs, podcasts, videos, online tools (formative and summative)

- Assessing the Cross-Curricular Standards and Goals Associated with STEAM Education (formative and summative)

- Going Beyond the Rubric (formative and summative)

You can share it in written form or create your version of assessment ideas using one of the following EdTech tools (they have free versions):

- Book Creator ebook – https://bookcreator.com/

- Piktochart Infographic (one of my favorites) – https://piktochart.com/

- Storyboard That Comic – https://www.storyboardthat.com/

- Google Site website – https://sites.google.com/

- A Podcast or Video

Student Examples

Two example student projects follow. One chose to use Book Creator while the other selected Piktochart. What was impressive to me was the professionalism of their work – both in their content and presentation, and that they created work that has the potential to be beneficial and useful for a wide audience of educators.

STE(A)M Assessments via Book Creator

STE(A)M Assessments via Piktochart

Assessing Maker Education Projects

Institutionalized education has given assessment a bad reputation; often leaves a sour taste in the mouths of many teachers, students, and laypeople. This is primarily due to the testing movement, the push towards using student assessment in the form of tests as a measure of student, teacher, principal, and school accountability.

Educators should be clear about why they include assessment in their instruction; be strategic and intentional in its use. For me, assessment really should be about informing the learner about his or her performance so that increased learning and future improvement result for that learner.

Assessment is the process of gathering and discussing information from multiple and diverse sources in order to develop a deep understanding of what students know, understand, and can do with their knowledge as a result of their educational experiences; the process culminates when assessment results are used to improve subsequent learning. (Learner-Centered Assessment on College Campuses: Shifting the Focus from Teaching to Learning)

As Hattie, Fry, and Fischer note in Developing “Assessment Capable” Learners:

If we want students to take charge of their learning, we can’t keep relegating them to a passive role in the assessment process.

When we leave students out of assessment considerations, it is akin to fighting with one arm tied behind our backs. We fail to leverage the best asset we have: the learners themselves. What might happen if students were instead at the heart of the assessment process, using goals and results to fuel their own learning? ((http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/feb18/vol75/num05/Developing-%C2%A3Assessment-Capable%C2%A3-Learners.aspx)

Maker Education and Assessment

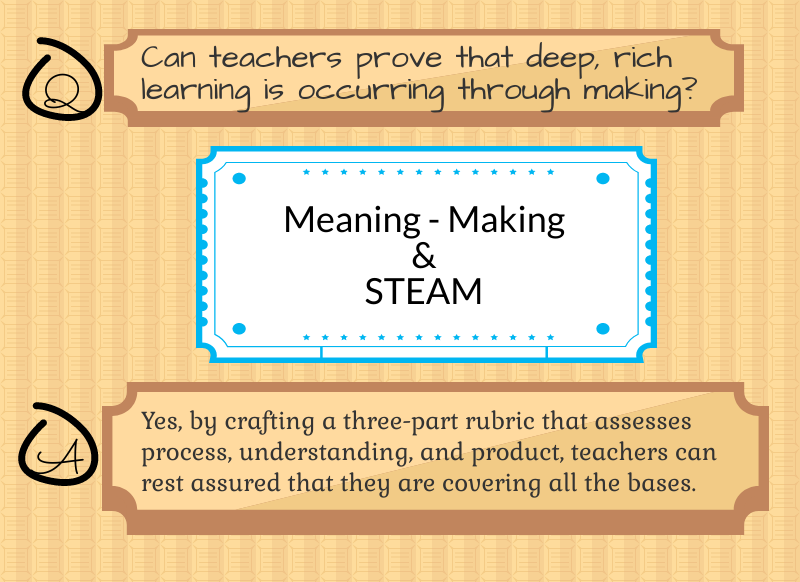

As maker education infiltrates more formal educational settings, there’s been and will continue to be efforts to include assessment as part of its implementation. It is important, though, to keep in mind the characteristics of maker education and the role assessment has within it.

Making innately provides evidence of learning. The artifact that results, in addition to the process that a student works through, provides a wealth of evidence, indicators, and data of their learning. Overall, though, assessing making comes back to the original (and difficult) question of what learning outcomes we’re seeking. Assessment is critical for understanding the scope and impact of learning, as well as the associated teaching, environment, culture, and content. (https://www.edutopia.org/blog/assessment-in-making-stephanie-chang-chad-ratliff)

Being a teacher, you’re constantly faced with having to assess student learning,” said Simon Mangiaracina, a sixth-grade STEM teacher. “We’re so used to grading work and giving a written assessment or a test. When you’re involved in maker education it should be more dynamic than that.” Part of the difficulty is that, in evaluating a maker project, teachers don’t want to undo all of the thinking that went into it. For instance, one of the most important lessons maker education can teach is not to fear failure and to take mistakes and let them inform an iterative design process — a research-informed variation of “guess and check” where students learn a process through a loop of feedback and evaluation. (https://rossieronline.usc.edu/maker-education/7-assessment-types/ from USC Rossier’s online master’s in teaching program)

I have my gifted students do lots maker activities where I meet with the 2nd through 6th graders for 3 to 5 hours a week. Since I do not have to grade them (not in the traditional sense as I have to write quarterly progress reports), I don’t have to give them any tests (phew!). I do ask them, though, to assess their work. I believe as Dale Dougherty, founder of MAKE Magazine, does:

[Making] is intrinsic, whereas a lot of traditional, formal school is motivated by extrinsic measures, such as grades. Shifting that control from the teacher or the expert to the participant to the non-expert, the student, that’s the real big difference here. Dale Dougherty

Christa Flores in Alternative Assessments and Feedback in a MakerEd Classroom stated:

In a maker classroom, learning is inherently experiential and can be very student driven; assessment and feedback needs to look different than a paper test to accurately document and encourage learning. Regardless of how you feel about standardized testing, making seems to be immune to it for the time being (one reason some schools skip the assessment piece and still bill making as an enrichment program). Encouragingly, the lack of any obvious right answers about how to measure and gauge success and failure in a maker classroom, as well as the ambiguity about how making in education fits into the common standards or college readiness debate, has not stopped schools from marching forward in creating their own maker programs.

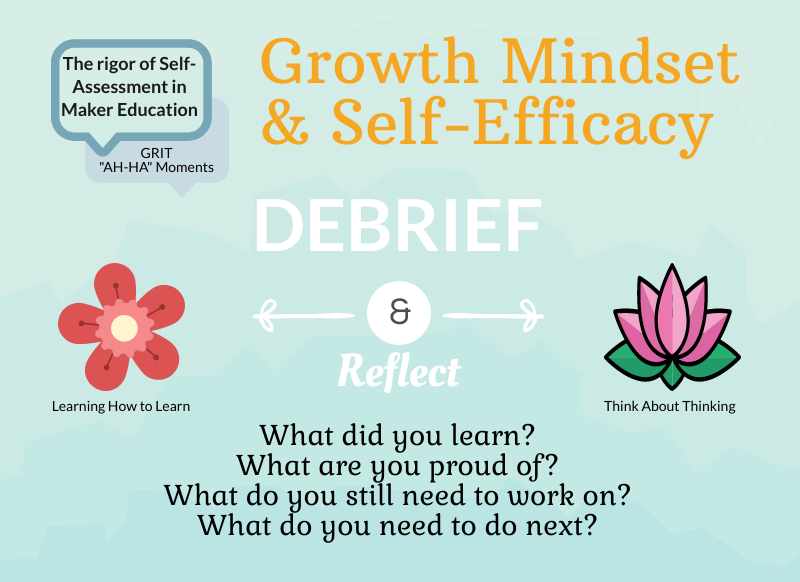

If the shift of control is given to the students within maker education settings, then it follows that the students should also be in charge of their assessments. One of the goals of maker education should be self-determined learning. This should include learners engaging in their own personal and personalized form of assessment.

Student self-assessment involves students in evaluating their own work and learning progress.

Self-assessment is a valuable learning tool as well as part of an assessment process. Through self-assessment, students can:

- identify their own skill gaps, where their knowledge is weak

- see where to focus their attention in learning

- set realistic goals

- revise their work

- track their own progress

- if online, decide when to move to the next level of the course

This process helps students stay involved and motivated and encourages self-reflection and responsibility for their learning. (https://teachingcommons.stanford.edu/resources/teaching/evaluating-students/assessing-student-learning/student-self-assessment)

Witnessing the wonders of making in education teaches us to foster an environment of growth and self-actualization by using forms of assessment that challenge our students to critique both their own work and the work of their peers. This is where the role of self-assessment begins to shine a light. Self-assessment can facilitate deeper learning as it requires students to play a more active role in the cause of their success and failures as well as practice a critical look at quality. (Role and Rigor of Self-Assessment in Maker Education by Christa Flores in http://fablearn.stanford.edu/fellows/sites/default/files/Blikstein_Martinez_Pang-Meaningful_Making_book.pdf)

Documenting Learning

To engage in the self-assessment process of their maker activities, I ask learners to document their learning.

We need to integrate documenting practices as part of making activities as well as designing, tinkering, digital fabrication, and programming in order to enable students to document their own learning process and experiment with the beauty of building shared knowledge. Documentation is a hard task even for adults, but it is not so hard if you design a reason and a consistent expectation that everyone will collect and organize the things they will share. (Documenting a Project Using a “Failures Box” by Susanna Tesconi in http://fablearn.stanford.edu/fellows/sites/default/files/Blikstein_Martinez_Pang-Meaningful_Making_book.pdf)

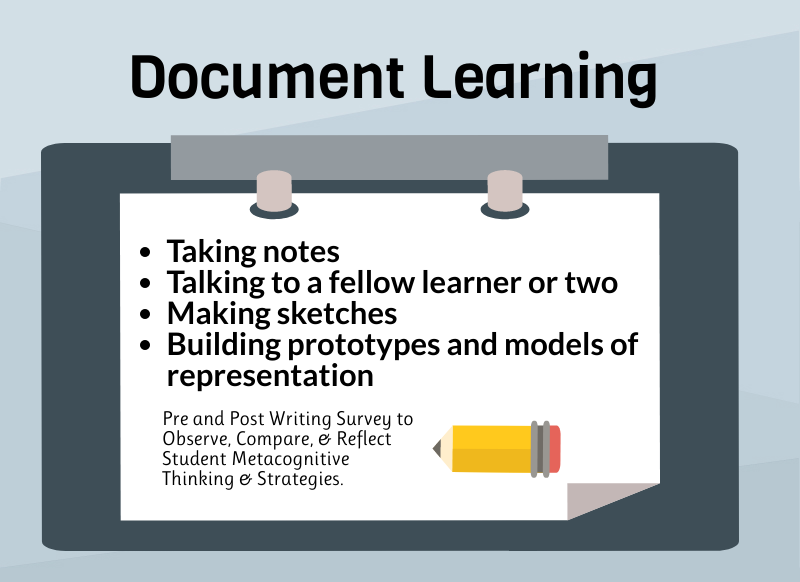

Documenting their learning can include one or a combination of the following methods:

- Taking notes

- Talking to a fellow learner or two.

- Making sketches

- Taking photos

- Doing audio recordings

- Making videos

(For more information, see Documenting Learning https://usergeneratededucation.wordpress.com/2016/04/08/documenting-learning/)

The folks at Digital Promise have the following message for maker educators regarding documentation:

Make the documentation an organic and expected part of the process. When documentation feels like it is added without reason, students struggle to engage with the documentation process. Help students consider how in-process documentation and reflection can help them adapt and improve the project they are working on. Help them see the value of taking time to stop and think.(http://global.digitalpromise.org/teachers-guide/documenting-maker-projects/)

Documenting learning during the making process serves several purposes related to assessment:

- It acts as ongoing and formative assessment.

- It gives learners the message that the process of learning is as important as the products of learning, so that their processes as well as their products are assessed. (For more information on the process of learning, see Focusing on the Process: Letting Go of Product Expectations https://usergeneratededucation.wordpress.com/2017/12/17/focusing-on-the-process-letting-go-of-product-expectations/)

Maker Project Reflections

Because many students haven’t had the experience of reflection and self-assessment, I ease them into this process. With my gifted students, I ask them to blog their reflections after almost all of their maker education activities. They take pictures of their makes, and I ask them to discuss what they thought they did especially well, and what they would do differently in a similar future make. Here are some examples:

Teacher and Peer Feedback

The learners’ peers and their educators can view their products, documented learning, and reflections in order to provide additional feedback. A culture of learning is established within the maker education community in that teacher and peer feedback is offered and accepted on an ongoing basis. With this type of openness and transparency of the learning process, this feedback not only benefits that individual student but also the other students as they learn from that student what worked and didn’t work which in turn can help them with their own makes.

The Use of Assessment Rubrics

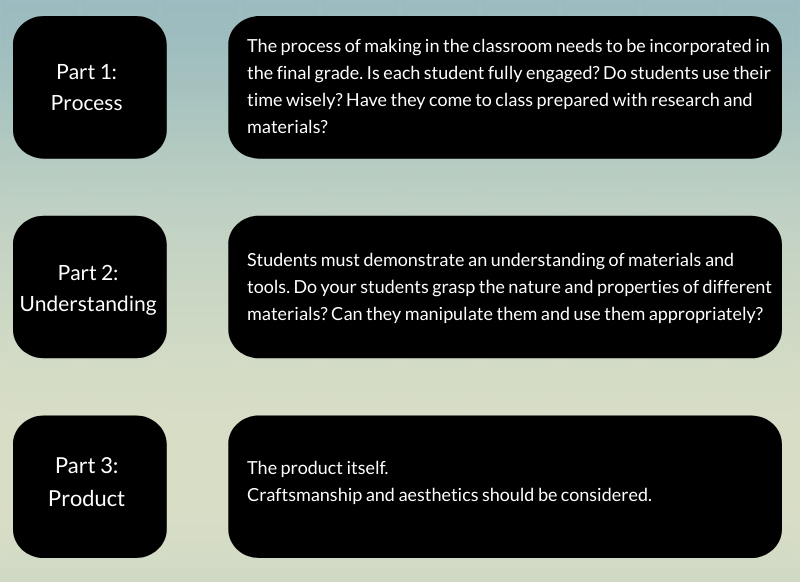

As a final thought, there has been some thoughts and efforts into using rubrics as assessment tools. Here is one developed by Lisa Yokana and discussed in Creating an Authentic Maker Education Rubric

I think rubrics, such as this, can be of value in assessing student work and/or having them assess their own work, but I prefer more open ended forms of assessment so the learners can but more of their selves into the process.

I Don’t Get Digital Badges

Digital badges appear to becoming the next, “new” thing in education. What follows is a description of digital badges as described by Digital Media and Learning:

A digital badge is an online record of achievements, the work required, and information about the organization, individual or other entity that issued the badge. Badges make the accomplishments and experiences of individuals, in online and offline spaces, visible to anyone and everyone, including potential employers, teachers, and peer communities.

In addition to representing a wide range of skills, competencies, and achievements, badges can play a critical role in supporting participation in a community, encouraging broader learning goals, and enabling identity and reputation building. For a learner, a sequence of badges can be a path to gaining expertise and new competencies. Badges can capture and display that path, providing information about, and visualizations of, needed skills and competencies. They can acknowledge achievement, and encourage collaboration and teamwork. Finally, badges can foster kinship and mentorship, encourage persistence, and provide access to ever-higher levels of challenge and reward (http://dmlcompetition.net/Competition/4/badges-about.php).

The proposed benefits of such a system would be a broader and deeper picture of skill sets acquired both in formal and informal settings.

Advocates of this vision for K-12 contend that such badges could help bridge educational experiences that happen in and out of school, as well as provide a way to recognize “soft skills” such as leadership and collaboration. Badges could paint a more granular and meaningful picture of what a student actually knows than a standardized-test score or a letter grade, they say (http://www.edweek.org/dd/articles/2012/06/13/03badges.h05.html).

https://wiki.mozilla.org/Badges

https://wiki.mozilla.org/Badges

The Functions of Badges

Daniel Hickey proposed four functions of badges in Intended Purposes Versus Actual Function of Digital Badges:

- Recognizing Learning. David Wiley has argued cogently that this should be the primary purpose of badges. If we focus only on purposes, then he may well be right. His point is that badges are credentials and not assessments.

- Assessing Learning. Nearly every application of digital badges includes some form of assessment. These assessments have either formative or summative functions and likely have both.

- Motivating Learning. If we use badges to recognize and assess learning, they are likely to impact motivation. So, we might as well harness this crucial function of badges and study these functions carefully while searching for both their positive and negative consequences for motivation.

- Evaluating Learning. Digital badges have tremendous potential for helping teachers, schools, and programs evaluate and study learning. At the minimum, just having a system for tracking all of the information included in all of the badges that a program awards might be very valuable.

As good playground and game designers understand, it really does not matter what the intended purposes are of the adult designers. Children and young people will approach and interact with the apparatus in ways that fit their own development and sensibilities. Based on past history, such as stickers in class or at home for good behavior; badges in scouts for accomplishments, I have a hunch kids will approach the gathering of badges as a form of rewards.

Badges As Rewards/As a Means for Motivation

It’s a fine line between working for the reward of the badges (think badge of honor or bragging rights) and for demonstrating a skill set. Although digital badges are being touted as a means of documenting one’s achievements, we cannot get away from the notion that learners will work towards getting badges for the rewards.

Many point to research that suggests rewarding students, with a badge for instance, for activities they would have otherwise completed out of personal interest or intellectual curiosity actually decreases their motivation to do those tasks (http://www.edweek.org/dd/articles/2012/06/13/03badges.h05.html).

The problems of using rewards for motivation have been discussed by Alfie Kohn and Daniel Pink. Alfie Kohn, an outspoken anti-reward proponent, notes that they can actual achieve outcomes in direct opposition of desired results.

Rewards are no more helpful at enhancing achievement than they are at fostering good values. At least two dozen studies have shown that people expecting to receive a reward for completing a task (or for doing it successfully) simply do not perform as well as those who expect nothing (Kohn, 1993). This effect is robust for young children, older children, and adults; for males and females; for rewards of all kinds; and for tasks ranging from memorizing facts to designing collages to solving problems. In general, the more cognitive sophistication and open-ended thinking that is required for a task, the worse people tend to do when they have been led to perform that task for a reward (http://www.alfiekohn.org/teaching/ror.htm).

Daniel Pink discusses a similar occurance in organizational settings:

We’re not mice on treadmills with little carrots being dangled in front of us all the time. What’s frustrating, or ought to be frustrating, to individuals in companies and shareholders as well is that when we see these carrot-and-stick motivators demonstrably fail before our eyes – when we see them fail in organizations right before our very eyes – our response isn’t to say: “Man, those carrot-and-stick motivators failed again. Let’s try something new.” It’s “Man, those carrot-and-stick motivators failed again. Looks like we need more carrots. Looks like we need sharper sticks.” And it’s taking us down a fundamentally misguided path.

Digital Badges as a Form of Gamification

There is an argument that digital badges will be successful due to their similarity to game mechanics. Terry Hick in How Gamification Uncovers Nuance In The Learning Process stated that:

A digital trophy system–if well-designed–offers the ability to make transparent not just success and failure, accolades and demerits, but every single step in the learning process that the gamification designer chooses to highlight. Every due date missed, peer collaborated with, sentence revised, story revisited, every step of the scientific process and long-division, every original analogy, tightly-designed thesis statement, or exploration of push-pull factors–every single time these ideas and more can be highlighted for the purposes of assessment, accountability, and student self-awareness.

But comparing the digital badge system to gaming behaviors is a weak one. Bron Stuckey, Quest Atlantis research fellow, succinctly puts it as “slapping a layer of badges over learning isn’t gamifying learning.”

There are several significant differences:

- The user is self-motivated. Gamers choose the games they play and their goals for using that game. They are mainly drive by intrinsic motivators. The leveling-up becomes the symbols of their personal achievements. In other words, the leveling up badge of recognition is a result of performance not the primary goal of playing the game (subtle but significant difference).

- Gaming provides continuous feedback about personal performance. Although claims have been made that digital badges can provide this type of formative assessment, most appear to be designed as a summative assessment – learners meet a set of pre-established criteria to earn a digital badge.

Who Decides?

Another possible flaw in and potential downfall of this system revolves the difficulties and dilemmas of deciding what the badges represent, how one earns the badges, and how badges will be standardized for recognition of “institutions” of learning and of employment. This lack of consensus about the meaning of badges will create further problems once the learner leaves that learning platform. What value will the badges have in unrelated institutions?

Other Alternatives

A purpose or rationale given for the use of digital badges is to provide evidence of specific skills sets that goes beyond courses taken and degrees earned. Randy Nelson of Pixar states that when choosing potential employees, he wants to see the proof of a portfolio not the promise of a resume (http://www.edutopia.org/randy-nelson-school-to-career-video). Digital badges have the potential to become a type resume on steroids – showing that skill sets have been achieved but not providing specific evidence and artifacts that demonstrate those skill sets. Given this age of personal websites, blogs, photo and video sharing sites, learners can easily leave a trail of competencies and skills via an aggregate of their achievements via some form of electronic portfolios. Here is a question to all of those who are considering developing or using digital badges for learning: If you wanted to evaluate someone for competency (e.g., for progressing to the next level of learning or for employment), would you prefer to see a digital badge or artifacts that provide evidence of that learning?

It is important to hack digital badges to explore potential intended and non-intended consequences of their implementation. Technology has sadly produced a learning society that easily gets seduced by each brand new shiny toy.

Why do we give tests? What purpose does it serve?

I absolutely have no idea why educational institutions use tests to presumably measure student learning. I believe that tests provide an illusion that something has been learned, one that all stakeholders; teachers, administrators, parents, and students, themselves, have bought into.

I do not give tests. I have taught undergraduate and graduate level college, gifted elementary students, middle school physical science and K-8 PE; and never give paper and pencil tests. One of my missions as an educator is to provide students with transferable life skills. I do not believe that the ability to take tests is one of them. Would a vast majority of learners say . . . “Wow, I can’t wait, we get to take tests at school today.” “I found that test totally engaging. I was in a state of flow”

Prior to going forward, let me clearly state that I believe that are qualitative differences between assessment, measure, and tests. I think that feedback and assessment are important aspects of the learning cycle, but am unclear how tests, in their traditional form, provide students with feedback that lead to increased personal performance. Human learning is often complex, multifaceted, and idiosyncratic so to attempt to quantify it, often to a single number, really diminishes and minimizes this incredible experience.

As Cathy Davidson discussed in How Do We Measure What Really Counts In The Classroom?

Education has not yet moved past the standardized assessment, which was invented in 1914. Frederick Kelly, a doctoral student in Kansas, was looking for a mass-produced way to address a teacher shortage caused by World War I. If Ford could mass produce Model T’s, why not come up with a test for “lower order thinking” for the masses of immigrants coming into America just as secondary education was made compulsory and all the female teachers were working in factories while their men went to the European front? Even Kelly was dismayed when his emergency system, which he called the Kansas Silent Reading Test, was retained after the war ended. By 1926, a variation of Kelly’s test was adopted by the College Entrance Examination Board as the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT). The rest is history.

But because the No Child Left Behind national law began requiring the standardized tests for all students since 2002, it takes them one to two years to retrain these great students not to think in terms of single-best-answer (multiple choice) options. They have to make them “unlearn” the skill of guessing the best answer from five available ones (a pretty useless skill in the workplace), and begin to “relearn” how to think about what they do or don’t really understand about a situation, who to go to in order to find out, and what they need to do to have the best results. In other words, whether we are 1st or 17th, we’re failing at testing what we really value in the workplace. There is an extreme mismatch between what we value and how we count.

Leon Nevfakh, in a Boston Globe article, discusses the implications of the Harvard cheating scandal in What to test instead

Being successful in today’s world, as we all now recognize, requires more than an ability to think quickly and recall facts on command. And our education system has, however fitfully, moved to address those values. The problem is that our tests still lag behind.

“[Historically], the testing industry, because it was pragmatic, only tested what it was easy to test,” said James Paul Gee, a professor at Arizona State University. “But as a parent, I don’t want you to just test what’s easy to test, I want you to test what’s important to test.”

In terms of developing more authentic assessments, Nevfakh notes:

Using new testing ideas like computer simulations, games, and stealth monitoring, they are trying to take what they believe is a huge and necessary leap—changing the test as we know it from a fixed measurement of what a student can remember on a particular day, to something far more dynamic and informative.

The researchers at the forefront of test design also have a bigger dream, rooted in the idea that tests aren’t just a static part of education, but can actively shape what teachers teach and what students learn. If you can really build smarter, more sophisticated tests, they say, you can change education itself.

Assessment as a Means for Developing a Sense of Achievement

They replaced the old spin bikes with some new ones at the health club where I work out. These new ones have a feedback monitor that provides feedback about effort via the RPM, watts, and gear level, The spin instructor told us that the recommended watts for a good workout is over 200. I started my workout as I always do, putting out my typical amount of effort. The watts indicator hovered between 100 and 125. Yikes! I have gone to two workouts using this monitor. I have reached, huffing and puffing, 200 watts on a few occasions, and attempt to keep it at around 150. I wasn’t able to reach 200 watts the first time and felt a great sense of achievement upon doing so during my second spin class with the monitor. Needless to say, these were some of the best spin workouts I have accomplished. I realized that the monitor made my spin performance into a type of game by me providing me with ongoing and continuous feedback and a way to level up.

I made the connection between my experiences on the spin bike and the need for humans to feel a sense of achievement.

Need for achievement (N-Ach) refers to an individual’s desire for significant accomplishment, mastering of skills, control, or high standards. The term was first used by Henry Murray[1] and associated with a range of actions. These include: “intense, prolonged and repeated efforts to accomplish something difficult. To work with singleness of purpose towards a high and distant goal. To have the determination to win”. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Need_for_achievement)

I began thinking about how all of this applies to the educational setting. I have a cynical view about assessments, most often in the form of tests, and how they are used at school. They are often contrived and separate from the learning process, and a measure of a student’s deficiencies. As such, students do not use information gleamed from the assessment process to improve their performance. As a deficiency model, rather than one that promotes a sense of achievement, students who do not achieve 100% proficiency feel as though they have failed in some way.

Assessment should be a continuous feedback loop, one that is integrated into the learning process, and where the feedback improves the competency of the learner. Assessments should be used as opportunities to develop competencies and the related sense of achievement.

Sal Khan discusses this problem of testing:

Regardless of whether they can prove proficiency in 70, 80, or 90 percent of the material, they are “passed” to the next class, which builds on 100 percent of what they should have learned. Fast-forward six months, and students are lucky to retain even 10 percent of what was “covered.”

This is a grand exercise in labeling and filtering students with arbitrary grades rather than teaching them. It is a hugely inefficient use of time and resources, but no one wants to notice, because it is the way things have always been done.

Perhaps the worst artifact of this system is that most students end up mastering nothing. What is the 5 percent that even the A student, with a 95 percent, doesn’t know? The question becomes scarier when considering the B or C student. How can they even hope to understand 100 percent of a more advanced class?

Ten years from today, students will be learning at their own pace, with all relevant data being collected on how to optimize their learning and the content itself. Grades and transcripts will be replaced with real-time reports and analytics on what a student actually knows and doesn’t know. (YouTube U. Beats YouSnooze U.)

This is why I believe that game-based learning is becoming popular and being promoted viable means for assessment.

As James Gee notes:

Games don’t separate learning and assessment. They are giving you feedback all the time about the learning curve you are on.

So what is the difference between a game or a machine giving feedback and a teacher giving a grade? How does all of this relate to intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation? Is getting feedback from a game extrinsic motivation? Does the external rewards gained through leveling up in a video game or gaining a badge by completing a series of competencies diminish the sense of accomplishment?

Judy Willis, A Neurologist Makes the Case for the Video Game Model as a Learning Tool:

It may seem counter intuitive to think that children would consider harder work a reward for doing well on a homework problem, test, or physical skill to which they devoted considerable physical or mental energy. Yet, that is just what the video playing brain seeks after experiencing the pleasure of reaching a higher level in the game. A computer game doesn’t hand out cash, toys, or even hugs. The motivation to persevere is the brain seeking another surge of dopamine — the fuel of intrinsic reinforcement.

Good games give players opportunities for experiencing intrinsic reward at frequent intervals, when they apply the effort and practice the specific skills they need to get to the next level. The games do not require mastery of all tasks and the completion of the whole game before giving the brain the feedback for dopamine boosts of satisfaction.

. . . which she further notes, helps students develop competencies and the related sense of achievement.

In the classroom, the video [game] model can be achieved with timely, corrective feedback so students recognize incorrect foundational knowledge and then have opportunities to strengthen the correct new memory circuits through practice and application. However, individualized instruction, assignments, and feedback, that allow students to consistently work at their individualized achievable challenge levels, are time-consuming processes not possible for teachers to consistently provide all students.

The best on-line learning programs for building students’ missing foundational knowledge use student responses to structure learning at individualized achievable challenge levels. These programs also provide timely corrective and progress-acknowledging feedback that allows the students to correct mistakes, build understanding progressively, and recognize their incremental progress.

How can all of these ideas influence how educators provide feedback to learners and opportunities to develop competencies along with the resultant sense of achievement?